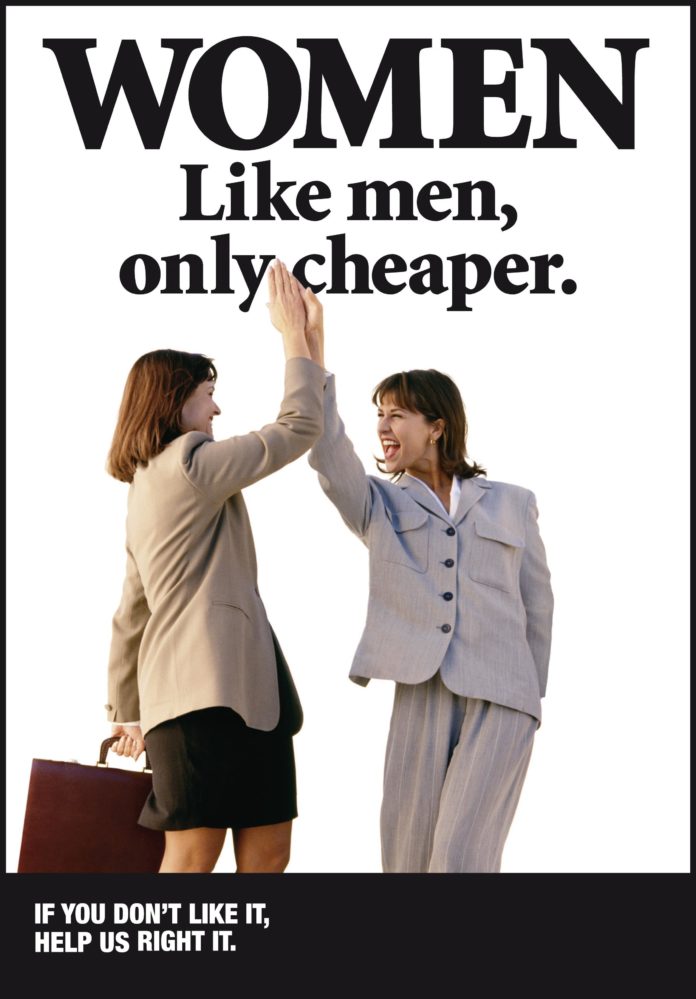

More women than men now enroll in college. More graduate and they earn better grades. But at every level of educational attainment, men still earn more money and the gap grows larger with time. Are we systematically underpaying women? If so, why would labor markets behave that way?

To some, the question is laughably simple: greedy men exploit women. This is true, but greedy capitalists exploit men too. Greed, not fairness, should lead to some rough market price of equivalent skill and experience unless talented women are somehow different from anything else that is bought and sold in quantity. Asserting that bosses are greedy and biased doesn’t explain much. After all, greedy bosses cheerfully bid up the price of copper. At the risk of commodifying half the population, it is useful to ask why are they not bidding up the price of talented women?

To some, the question is laughably simple: greedy men exploit women. This is true, but greedy capitalists exploit men too. Greed, not fairness, should lead to some rough market price of equivalent skill and experience unless talented women are somehow different from anything else that is bought and sold in quantity. Asserting that bosses are greedy and biased doesn’t explain much. After all, greedy bosses cheerfully bid up the price of copper. At the risk of commodifying half the population, it is useful to ask why are they not bidding up the price of talented women?

There are, it turns out, many reasons that women are paid less than men. Most raise issues worth addressing, whether or not they conform neatly to the “glass ceiling” narrative. The reasons for pay inequality include:

Discrimination. This happens a lot and is much more prevalent in Silicon Valley than is widely acknowledged. Goodyear Tire famously paid women less then men who did the same work and took pains to conceal their policy. The Lilly Ledbetter Equal Pay Act resulted when Ledbetter discovered the facts and sued Goodyear. It is interesting to ask how the story would have been different if the fact of discriminatory pay had been known all along. Would women have demanded raises? Or would they have changed jobs and, if they did, would the result have been higher or lower aggregate pay for women?

Motherhood-induced time off and reductions in work hours. Part of the reason that women earn less is that they take more time off to raise kids. When women first graduate, pay differences are less than they will ever be, for reasons we will touch on later. By age 30 however, significant differences emerge. Harvard’s Larry Katz and Claudia Goldin joined with Chicago’s Marianne Bertrand to follow nearly 3,000 M.B.A.’s over 15 years. The women started off making 88 percent as much as men, but 10 to 15 years later, they made only 55 cents for every dollar of men’s pay.

The scholars accounted for differences in grades, course choices, and previous experience. Their conclusion: kids kill careers. They found that the women’s pay deficit was almost entirely because women interrupted their careers more often and tended to work fewer hours. The rest was mostly explained by career choices: for instance, more women worked at nonprofits, which pay less. A subsequent study by scholars at CUNY, also published by NBER, largely confirmed this finding.

This explanation dodges the underlying question of why are the financial penalties to taking time off so high? After all, if between age 30 and 35, I take a year of maternity leave and work 4 days a week for six or seven years, I might sacrifice two years of work experience between age 30 and 40. Meaning that a 40 year old woman who is a mom has the same experience as a 38 year old man who contributed zero to raising his kids.

Is there really something so magical about the fourth decade of life that missing some work justifies a permanent economic penalty? A Labor Department study completed in 1992 concluded that time off for career interruptions explain only about 12% of the gender gap (not counting part time work and experience effects and, unlike Goldin, et al, they did not focus only at MBAs). There remains of course, the threshold question of whether women should be the default caretaker and disproportionately bear the professional cost associated with raising children. In many households of course, they do not — but this is still the exception.

Experience gaps. People with more experience are paid more if experience translates into superior productivity. Women who leave the workforce to have children pay twice: once because they work fewer hours and a second time because they accumulate less experience. This is reflected in their earnings when they return. This gap should be erased when a woman has been back at work awhile and research indicates that it takes about four years if a woman returns to work full-time, which many do not.

Occupational differences. To the extent that some occupations are more heavily male and higher paid while others are more heavily female and lower paid, earnings gaps may indicate a problem of occupational mix. As women enter traditional male occupations, as has occurred very widely during the past 40 years, these effects lessen. Some scholars figure that most of the reduction of the gender gap during the last four decades is due to women entering traditionally male occupations; others determine that only a third of the gap was closed this way.

Most studies do not ask why a profession earned less money to start with. After all, pay in many professions (including teaching) declined as they became more female and pay in some current professions (including law) appears to be going through something similar. Scholars who study these differences often have trouble sorting out historic patterns of gender discrimination from productivity or skill related pay differences.

Attraction to less successful industries or firms. Some industries and some companies pay both men and women less than do other industries. If women choose these industries or companies disproportionately, their average earnings will be lower compared to average men’s earnings, even if they are receive equal pay for equal work. Lower productivity industries, notably service intensive retail, education, and some health care, pay both women and men less than do higher productivity industries. The problem, of course, is that pay gaps persist within industries, not simply between them — but it is the averages that make for enticing infographics. A Labor Department study completed in 1992 concluded that 22% of the gap between men and women’s earnings could be explained by variation in industries.

In some cases, women also seem to choose firms within an industry that pay both men and women less (perhaps because they offer more flexible work arrangements). Janice Madden studied women stockbrokers, for example, whose pay is strictly performance-driven. She documented that although women were assigned inferior accounts and performed as well as men when they were not, a relatively small share of the total pay gap was the result of this unequal treatment. Although the industry paid women quite well, women were more likely than men to work in smaller, less successful brokerages.

Lower expectations and inferior bargaining. Most women do not bargain for their salaries as aggressively as do most men. I once had to explain to an Engineering VP I had hired that I had expected her to counter my initial compensation offer, not simply to accept it. As a result, I was underpaying her relative to her colleagues and industry peers. I was mildly annoyed as I explained that I would pay her more than she agreed to but expected her to take a more aggressive view of her economic value in the future.

There is plenty of evidence that this example was not unusual, even though my response may have been. The problem begins with expectations: women expect to be paid less than men do. A 2012 survey of 5,730 students at 80 universities found that women expected starting salaries that were nearly $11,000 lower than their male classmates. Women veterinarians, who bill their own clients at rates they set, were found to set their prices lower than their male colleagues and to more frequently “relationship price” meaning not charge friends or clients for small amounts of work. A similar effect occurs in law firms, where a lucrative partnership often depends on billed hours. The most prominent scholarly work in this area is by Linda Babcock at Carnegie Mellon, whose book title captured her major finding: Women Don’t Ask. Babcock realized the problem when she noticed that the plum teaching assistant positions at her university had gone to men who had bothered to ask about them, not to women, who expected them to be posted somewhere.

The effect on women of not negotiating is huge. According to Babcock, women are more pessimistic about the how much is available when they do negotiate and so they typically ask for and get less when they do negotiate—on average, 30 percent less than men. She cites evidence from Carnegie Mellon masters degree holders that eight times more men negotiated their starting salaries than women. These men were able to increase their starting salaries by an average of 7.4 percent, or about $4,000. In the same study, men’s starting salaries were about $4,000 higher than the women’s on average, suggesting that the gender gap between men and women’s starting salaries might have been closed had more of the women negotiated. Over a professional lifetime, the cost to women of not negotiating was more than $1 million.

Fortunately, this is pretty easy to fix. Women can learn quickly that everything is negotiable. The Jamkid pointed me to a recent investigation by his teacher John List at the University of Chicago, showing that given an indication that bargaining is appropriate, women are just as willing as men to negotiate for more pay. List finds that men remain more likely than women to ask for more money when there is no explicit statement in a job description that wages are negotiable.

Fortunately, this is pretty easy to fix. Women can learn quickly that everything is negotiable. The Jamkid pointed me to a recent investigation by his teacher John List at the University of Chicago, showing that given an indication that bargaining is appropriate, women are just as willing as men to negotiate for more pay. List finds that men remain more likely than women to ask for more money when there is no explicit statement in a job description that wages are negotiable.

Although legislation and litigation will surely be useful to discourage and penalize employers who systematically discriminate against women at scale, as WalMart is alleged to have done, most of the forces that contribute to inappropriately low pay for women will not be remedied in court. Two policy remedies however, could make a large difference and are politically achievable.

The first is paid parental leave. Paid leave for new parents is essentially a tax on non-parents (we already tax non-parents by allowing parents to deduct children as dependents). This makes sense — we want to reduce the economic penalty associated with having children. Every modern country except for the United States grants mothers and fathers the right to take time off work with pay following the birth or adoption of a child. European countries provide a period of at least 14 to 20 weeks of parental leave, with 70 to 100% of wages replaced. These countries also provide paid parental leave subsequent to this, although the duration of the job-protection and leave payment differs substantially across nations. The total duration of paid leave exceeds nine months in the majority of advanced countries. Canada, for example, currently provides at least one year of paid leave, with around 55% of wages replaced, up to a ceiling.

California is the only state that currently requires paid parental leave. Initial evidence suggests that the act has doubled maternity leave from three to seven weeks (barbaric by European standards) and raised the wages of new mothers by 6-9%. It’s a start, but we should join the modern world, and perhaps follow Denmark, which last I checked required that husbands take equal time away from work on the birth of a child in order to minimize the long term impact on women’s earnings. To those who worry that by subsidizing overpopulation in a capacity constrained planet, I would point to declining birth rates throughout Europe and the realization, which is slowly beginning to dawn on the world, that we face far more threats from low birth rates at the moment than we do from high ones.

The second step we could take is to force employers to disclose wage disparities among people who do the same work. This requirement needs a careful touch and FASB/SEC rule-making, but if a public company had to disclose the difference in pay between men and women by occupational category, it would quickly become a benchmark that everyone from board members to managers would need to look at and live with. Scholars and consultants would quickly compare businesses. Websites like Glass Door would post comparisons. Companies would feel pressure to either justify disparities with additional data (showing, for example, that men had more experience or more training within the same occupational category) or face demands to explain themselves. Women would be emboldened by data to ask for their due. These metrics would not be susceptible to industry or occupation differences, nor would they disclose salaries – only the percentage difference between men’s pay and women’s.

It might also begin a deeper, more fact-based, discussion about the sources of economic inequality. And such a disclosure would quickly expose the most embarrassing economic fact of all: some men — but relatively few women — are shockingly overpaid.