Imagine a service business whose core processes have not changed since medieval times, economically dependent on huge federal subsidies, and protected by a system of self-accreditation designed to exclude rivals. Imagine that the resulting enterprises held a monopoly on accrediting talent and exploited this advantage by overcharging customers and wasted the resulting revenue on guarantees of lifetime employment for senior employees, on massively expensive facilities and professional sports teams, and on protecting a comically inefficient bureaucracy. Who would put up with such a mess?

Welcome to American colleges and universities, which are both the envy of the world and ripe for disruption. Universities are the envy of the world because they are in two businesses: research and teaching. The research business is globally competitive if measured by peer-reviewed publications and patents — although somewhat less so if measured by the usefulness and reproducibility of the research.

The teaching part of the business is what Americans pay about $350 billion for annually. It would seem to be a soft target. It is, after all, run by tenured scholars whose idea of competition is a snarky jibe in the faculty lounge. The dons have allowed their costs to not only rise faster than family incomes, but faster than health care costs, which is a real achievement. Nonetheless, the university monopoly on certifying talent has conferred long term advantages. As Kevin Carey noted in a recent New Republic article,

“The historic stability of higher education is remarkable. As former University of California President Clark Kerr once observed, the 85 human institutions that have survived in recognizable form for the last 500 years include the Catholic Church, a few Swiss cantons, the Parliaments of Iceland and the Isle of Man, and about 70 universities. The occasional small liberal arts school goes under, and many public universities are suffering budget cuts, but as a rule, colleges are forever.”

Small wonder that thousands of startups are now focusing on the market for higher education. Even the inventor of disruption, Clayton Christensen, has declared that online technologies will thoroughly disrupt education at all levels. He predicts that half of all K-12 classes will be taught online by 2019.

During the past five years, online higher education has gone mainstream. The Sloan Foundation estimates that more 30% of all enrolled college students, some six million people, participated in on-line learning at accredited U.S. colleges and universities in 2011 and that the U.S. market for online higher education grew 12-14 percent annually between 2004-2009.

Many educators are realizing that the explosion of online education not simply due to its lower cost; it is often higher quality as well. Sometimes this is because of dramatically higher investment in course and instructor development. Christensen, who teaches at Harvard, notes that the largely online University of Phoenix spends about $200 million each year developing online teachers and highlights a key difference with traditional universities:

“..Harvard defines research as creating new knowledge, while The University of Phoenix defines it as finding new ways to provide knowledge. It blows the socks off of us in their ability to teach so well.”

The occasional small liberal arts school goes under, and many public universities are suffering budget cuts, but as a rule, colleges are forever.

Online education is quickly killing the in-class lecture, since recorded lectures have obvious advantages. Students can watch them when they are ready — after they are off work or when the kids are asleep. They can replay the confusing bits or skip the obvious parts. Most important however, is that the lectures themselves are more likely to delivered by world class teachers like Norman Nemrow, whose online accounting course has been taken by several hundred thousand students or by Walter Lewin, the MIT physicist whose lectures are shown on television. Supposedly over five million people have taken his intro to physics course.

Technology is improving classrooms as well, enabling instructors to measure progress and tailor the course to the needs of each student. Modern learning management systems provide live seminars with multi-location live video, backchat, social media, and many other capabilities not available in a classroom. Quizzes can be graded instantly so that both faculty and students get feedback fast enough to change course. Algorithms distill questions from thousands of students so that they can be answered either live or off-line. Students can undertake projects online with “classmates” who have never been on the same campus — or even the same country.

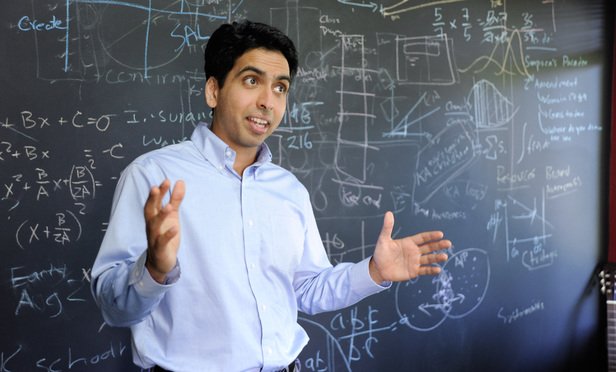

This is a time of vast experimentation with online education technologies. Two years ago, the Kahn Academy began to attract huge notice as a self-tutoring tool based on the brief lectures of one talented teacher. A year ago, 2U closed a large Series C and got very serious about providing major universities with technology, marketing, and course development assistance. A month ago, Google’s self-driving car maven Sebastian Thrun gave the talk at BLD in Munich that launched Udacity after 160,000 students from around the world completed his Stanford-based online computer science course (268 students achieved perfect scores on all the quizzes). In October, Knewton, an education technology startup, raised $33 million in its 4th round of funding to roll out its adaptive online learning platform. Earlier this year, Apple launched a suite of authoring and course scheduling tools to allow universities to move content to iTunes University. Only yesterday, ShowMe launched its 2.0 platform that takes the Kahn Academy model and makes it social — anyone can use the platform to teach anything.

This is a time of vast experimentation with online education technologies. Two years ago, the Kahn Academy began to attract huge notice as a self-tutoring tool based on the brief lectures of one talented teacher. A year ago, 2U closed a large Series C and got very serious about providing major universities with technology, marketing, and course development assistance. A month ago, Google’s self-driving car maven Sebastian Thrun gave the talk at BLD in Munich that launched Udacity after 160,000 students from around the world completed his Stanford-based online computer science course (268 students achieved perfect scores on all the quizzes). In October, Knewton, an education technology startup, raised $33 million in its 4th round of funding to roll out its adaptive online learning platform. Earlier this year, Apple launched a suite of authoring and course scheduling tools to allow universities to move content to iTunes University. Only yesterday, ShowMe launched its 2.0 platform that takes the Kahn Academy model and makes it social — anyone can use the platform to teach anything.

Universities are developing their own online education initiatives, often plagued by a terrifying thought: what if online education is just another form of digital media? They know full well that that as books, movies, and music, moved online, few incumbents survived. In each case:

Content was disaggregated and mashed. Just as record albums were broken into songs, ringtones, and clips, educational content is unlikely to remain entirely within current disciplines or courses. Literature will not remain separated from history, nor calculus from chemistry. As technology makes it easier to recombine and repurpose courseware, it may become possible for two students to complete the same course without confronting the same content in the same sequence or manner. New forms of learning will produce certifications not limited to degrees, concentrations, or even courses.

Engagement became social. Digital movies benefitted Hollywood much less than YouTube and Netflix. It should not surprise us to see more learning become self-paced, socially certified, and delivered outside of colleges and universities. Startups may increase the demand for formal education, but they could also substitute for it just as many of the needs once filled by campus fraternities or alumni associations are now met by online social networks. This does not mean the end of classrooms, which can be highly social. It probably spells the end of instructor-centric teaching however.

Value shifted from content creators to aggregators. Book publishers and music labels learned that aggregators of content (Amazon and iTunes) hold a lot of cards. Will universities aggregate and distribute high quality educational content regardless of its origin? Or will universities, like film studios, attempt to remain relevant by offering exclusive, premium-priced, high-quality, proprietary content protected through careful online distribution and syndication? Top universities are betting on the Hollywood model, which is not only under sustained attack, but presumes producers who control their IP. Universities, in contrast, rarely limit the ability of their faculty to sell lectures and other courseware to the highest bidder, even though the university paid the professor to produce the content. In no other industry is such theft conceivable — a fact that Udacity will not be the last to exploit.

The product went global. Books, movies, and music are licensed or sold in tightly controlled, nationally bounded markets, but digital media is naturally global because there are far fewer natural distribution barriers. This means more customers, which is why universities are now lusting after talented and wealthy Indian and Chinese students who are (at the moment anyway) willing to pay US-type tuition for a degree from a globally prestigious institution.

Prices fell as comparison shopping became easier. It appears that the revenue optimal price for eBooks is between $2 and $5, depending on the author and in some cases the publisher. For songs it is between $1-$2, forcing record labels and publishers to seek entirely different business models to monetize their content. As a result, many of media markets actually shrank as they went online (if you only measure product sales. In music, for example, the market is about the same size, because concerts and merchandise make up for losses in record sales).

The response of universities to the rise of online education is like the response of Barnes and Noble to online bookselling. Faced with the rise of Amazon.com in the 1990s, the chain store simply created barnesandnoble.com. When Amazon launched the Kindle, they launched the Nook and merchandised it in their increasingly irrelevant bookstores. But the winner of this contest will of course be the company that is not forced to carry the cost of several hundred bookstores. Open Yale, MIT’s Open Courseware and MITx courses, Stanford’s Massively Open Online Courses including Coursera, and many others like it all share the Barnes and Noble problem: they need to price their offering to pay for extraordinarily high fixed cost institutions. Their disruptors do not.

Barnes and Noble charges customers for a wide range of activities unrelated to book purchases. It designed many of its stores as community centers where authors and could meet readers. It built fun sections for kids to discover books. It integrated Starbucks in many locations. But books are simply not going to be sold in stores much longer, so these activities added more cost than value and ended up making the problem worse. Likewise, many institutions of higher education support multiple activities with tuition: research, sport, socialization, teaching, and credentialing. Online education exposes the fault lines between these different businesses, just as Amazon did with Barnes and Noble.

Research. Top schools recruit faculty based on their ability to contribute new knowledge to their field not on their ability to teach. This is terrific for graduate students, who apprentice and occasionally indenture themselves to senior faculty, but suboptimal for undergraduates because the correlation between insightful research and capable undergraduate teaching is somewhere between weak and negative. Once undergraduates can receive a higher quality education at a lower cost by studying online, many will do so. Once Amazon made books cheaper, nobody wanted to pay for those kids play areas — not even people who liked them.

Sports. That giant sucking sound is money draining from university budgets to support massively wasteful professional sports programs — while managing to abuse college athletes in the process. Intercollegiate sports are fine. Division 1 football and basketball is a scandal — and both universities and the NCAA know it.

Teaching. Teaching and learning are rapidly becoming another online interactive social media. Some online learning will doubtless be indistinguishable from games. This part of what a university does will be rapidly mashed, commodified, and redistributed, just as books and movies have been.

Socialization. Residential undergraduate programs deliver to young people a group of peers and the experience of learning independently with them. Some of what the university provides is in loco parentis — a structured environment for 18-22 year olds to transition to self-sufficiency as they learn. The question is how much families will pay for this service. As high quality online education becomes universally available, middle class families will be very tempted to forgo residential colleges for their kids. Now that families cannot enhance their incomes by working longer hours, sending a second adult to work, or borrowing easy money against overvalued homes, families will be willing to cut back on college expenses if it does not compromise the quality of their children’s education.

Credentialing. Credentials are necessary for employers and future education institutions to distinguish between similar candidates. Many markets with this problem rely on brands or other signaling effects (watch how you select wine next time you are confronted with dozens of plausible choices). University degrees emerged long ago as a critical signal of professional capability independent of what the degree holder knows. Part of this is because of selection effects, as Malcom Gladwell explained some years ago:

“Social scientists distinguish between…treatment effects and selection effects. The Marine Corps, for instance, is largely a treatment-effect institution. It doesn’t have an enormous admissions office, grading applicants along four separate dimensions of toughness and intelligence. It’s confident that the experience of undergoing Marine Corps basic training will turn you into a formidable soldier.

A modeling agency, by contrast, is a selection-effect institution. You don’t become beautiful by signing up with an agency. You get signed up by an agency because you’re beautiful.”

Top-tier universities produce top graduates by accepting applicants who are very likely to succeed — they trade heavily on selection effects. I once published a proposal in the campus newspaper challenging the Dean of the Harvard Business School to compare people who were admitted to HBS but did not attend with those who were admitted but did attend to see if the school was adding value or simply selecting people who were going to succeed anyway. He showed little enthusiasm for my research proposal, although other scholars (including Alan Krueger, who now chairs Obama’s Council on Economic Advisors) have since documented these selection effects. HBS does not produce successful managers like the Marines produces soldiers. It recruits them like a modeling agency does.

Treatment effects also create signals, whether anybody learns anything or not. Imagine that you have two job candidates who 25 years earlier attended the same school and took the same courses. One candidate failed every course and did not graduate. The other got straight As in the courses and graduated with honors, but has forgotten 100% of the material. Neither currently knows anything that they learned in college. But if this is all the information you had, you would hire the successful student — you’d be crazy not to. You have a signal that this person is capable of hard work and learning, even if they don’t retain it 25 years later. In labor markets, signaling matters a lot and university degrees are powerful signals. Online education will not quickly change this — although the creation of alternative credentialing mechanisms may.

Who decides what signal a degree sends? Employers do. If Google or Goldman begin hiring software engineers or managers who received their professional degrees online, the value of elite professional degrees will come into question. As a future post will detail, this is very likely to happen, since the knowledge and skill imparted by most professional degree programs can more easily be standardized, sequenced, and captured on standardized tests than undergraduate education can. Universities are rushing to offer professional degrees online because because students are willing to pay high tuition to finance a degree that will significantly increase their earnings. If competition from online professional degree programs pressures schools to reduce either tuition or admissions requirements, universities will see their professional degree cash cow led to slaughter. For this reason, better known universities hope fervently that dozens of competing online degree programs to emerge, saturate the market, and preserve the signaling value of the premium degree they offer.

As high quality education moves online, it will kill the weakest first: those schools that charge more and deliver less. Elite research universities will be forced to trade heavily on their brand and the signaling value of their credential, which may become easier as online programs proliferate and education markets become even more global. The experience of going to college may never be reducible to interactive social media — but classroom teaching of many subjects surely is. This is especially true for STEM and foreign languages where the US needs all the help it can get.