It is by a considerable distance the finest American speech of the twentieth century. In its staging and phrasing, it consciously evoked the finest American speech ever, delivered nearly one hundred years earlier nearly one hundred miles away.

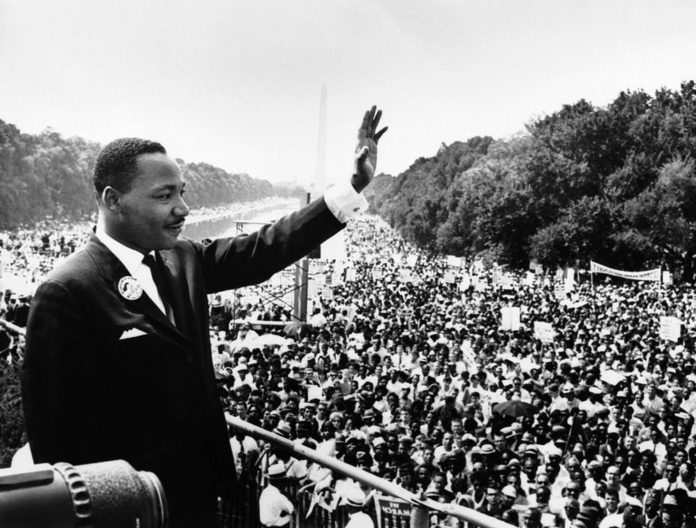

Watch it, or read Martin Luther King, Jr.’s speech to hundreds of thousands of people who gathered for the 1963 march on Washington here, then judge for yourself:

It is better than our best presidential inaugurals. FDR, JFK and Reagan’s firsts are each considered best in class by most historians. It’s better than the presidential speeches that rallied America through crisis, including FDR’s Day of Infamy, Reagan’s Challenger remarks, or JFK’s address on the Cuban Missile Crisis. It is better than the finest partisan barn burners including convention keynotes from Barbara Jordan in ’76, Jesse Jackson or Mario Cuomo in ’84, or Barrack Obama in ’04.

Martin Luther King, Jr.’s speech was fired in a tough, divisive, complex, and bitter political struggle of the sort that Americans today under age forty have never experienced. The march on Washington itself was a highly controversial tactic. As buses jammed into Washington, DC from around the nation, President Kennedy increased political pressure on the marchers. He wanted King to tone down his demands and to not denounce the federal government for its failure to safeguard civil rights or to protect protesters from police violence. King agreed to so many of these demands that Malcolm X denounced the march as the “Farce on Washington” and suspended any Nation of Islam members who attended.

But then King delivered a soaring, poetic, yet biting address that has been studied for years for its cadence and metaphor as well as its political values and claims. Like most of America’s great orators, King did not separate church and state — he spoke confidently of faith, redemption, charity, caring, and community. He was, after all, leading the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

The speech was amplified by a new technology: television broadcast by national networks. America did not know King and was not expecting a 34 year old black man with a PhD to methodically, eloquently, and passionately call the nation to its better self. White America, whether rich or poor, northern or southern, urban or rural, liberal or conservative had never seen a deeply intelligent, militant, nonviolent black minister demand that we overcome prejudice, confront injustice, and honor black Americans. I turned 11 years old the day before the speech and recall clearly the discomfort that King caused my family and neighbors during the summer of ’63 and the even hotter summers that followed.

The speech made King the visible and irrevocable leader of the US civil rights movement. Within months, he became the youngest person in history to receive the Nobel Peace Prize — arguably the most prestigious award on the planet.

The march and the speech inspired the 1964 Civil Rights Act — the most far-reaching piece of legislation in the twentieth century (a bill that survived the longest filibuster in US history and passed Congress mainly as a tribute to the slain JFK. After signing the bill, Lyndon Johnson — a progressive Texan who knew how to count votes — reportedly lamented that “we have lost the South for a generation”). Two generations later, he appears to have been optimistic.

On King’s birthday, check out his speech. It is worth your commemoration and study.