Intel founder Gordon Moore famously observed that chip density doubles about every two years. Thanks to Moore’s Law, computer processing gets cheaper exponentially, not arithmetically.

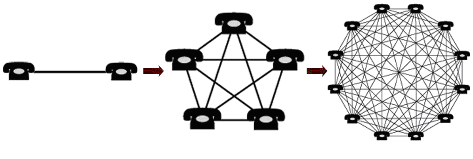

Metcalfe’s Law is a lesser known but equally powerful law concerning not hardware but the economics of networks (specifically a telecommunications network, but the Law appears to apply more broadly). It says that the value of a network is proportional to the square of the number of users. A telephone is an easy example: the first one is useless, the second one can call only one other machine, but the millionth one increases however slightly the utility of each of the other machines (assuming they can connect. You have to count Chinese phones as a separate network if you don’t speak Chinese).

Plenty of people debate whether Metcalfe (who invented Ethernet and founded 3Com) got the math right, but the principle seems sound and goes a long way to explaining what economists like to call network effects: businesses in which each participant is better off when a new participant joins. This is a topic for another day, but Microsoft, Google, eBay, Amazon third party sales and a lot of other “can’t live without them” businesses have taken powerful advantage of network effects and Metcalfe’s Law underpins a lot of the economics at work.

Plenty of people debate whether Metcalfe (who invented Ethernet and founded 3Com) got the math right, but the principle seems sound and goes a long way to explaining what economists like to call network effects: businesses in which each participant is better off when a new participant joins. This is a topic for another day, but Microsoft, Google, eBay, Amazon third party sales and a lot of other “can’t live without them” businesses have taken powerful advantage of network effects and Metcalfe’s Law underpins a lot of the economics at work.

Even less well known than Metcalfe’s law is what arrogance and alliteration led me some time back to term Manley’s law, which states that all media wants to be digital and free at the margin. Like Moore’s or Metcalfe’s theorems, this is a hypothesis that can be falsified: Moore will be proven wrong the day chip density stops increasing, Metcalfe the day that bigger networks are not more valuable, and me the day that media stops becoming digital or freely exchanged. By now you have noticed that Manley’s law is in some respects a corollary of the other two. I doubt that it would exist except as a by-product of Moore and Metcalfe.

Manley’s Law is having a good run lately. For simplicity, let’s define media as books, movies, and music — although you could apply it to photographs and several other media types. Music digitized first simply because the files are smaller and people want to listen to the same song more often than they want to read the same book or see the same movie.

Music

Manley’s law hit the music business so fast and that the New York Times referred this week to “the anarchy sweeping the music industry”. Music became a digital media on August 17, 1982, when ABBA’s The Visitors became the first CD to roll off an assembly line at a Philips factory in Langenhagen Germany. In 25 years, analog vinyl LP albums have been reduced to an audiophile niche and cassettes and 8-tracks have mercifully disappeared altogether.

Manley’s law hit the music business so fast and that the New York Times referred this week to “the anarchy sweeping the music industry”. Music became a digital media on August 17, 1982, when ABBA’s The Visitors became the first CD to roll off an assembly line at a Philips factory in Langenhagen Germany. In 25 years, analog vinyl LP albums have been reduced to an audiophile niche and cassettes and 8-tracks have mercifully disappeared altogether.

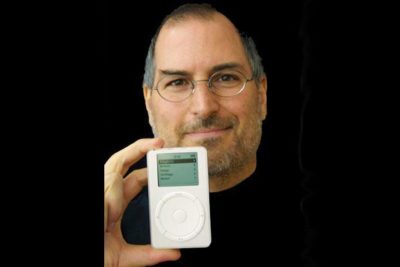

Five years ago, iTunes made music commercially downloadable and since then, Tower Records, Musicland, Sam Goody and many smaller retailers have disappeared or been absorbed by chain discounters like Wal-Mart and BestBuy. This week Apple Computer announced that in January iTunes passed Wal-Mart to become the largest music retailer in the United States. CD sales have declined every year since Apple launched iTunes and in recent years CD sales have fallen in double digits each year. In 2006, 38% of US teens did not by a single CD. In 2007, the number was 48%.

So music became digital, but iTunes does not make music free at the margin.

The company has sold four billion tracks at a buck each, so when is music going to be free? Apple has sold perhaps 130 million iPods (it passed 100 million a year ago). That works out to an average of 33 iTunes tracks for each device. But iPods hold somewhere between hundreds and thousands of songs, so even if you ac count for obsolete devices, you have to ask what people are putting on their iPods if not paid music (or videos) from iTunes? Answer: they are loading them with free content.

Some of the free content is ripped CDs — and not all of these were paid for (what, after all, are people buying hundreds of blank CDs for, anyway?). Some free tracks come from MySpace, which according to a Forester analyst now has more than 8 million artists and bands (and today announced a deal with several music labels to compete with iTunes). iTunes has the largest music catalog in the world with 6 million tracks — so 8 million bands and artists is a really large number. Some of these tracks have never sold a single

copy â but the experience of most long tail media markets is that there are a lot fewer of these than you might think.

Describing the role of MySpace in music, Forester notes that “Acts including Lily Allen, Sean Kingston, Arctic Monkeys, and Dane Cook were discovered on the site by users. (I don’t know most of these artists, although I saw a fast-rising Lily Allen at South by Southwest last year and was impressed).

P2P file sharing, denounced by the music industry as illegal downloading, continues to grow by double digits each year. Growth may be slowing, but only BigChampagne knows for sure. BigChampagne is a smart company that has tracked file downloading for years. They sell information about which demographic groups download what music in different parts of the country. Record companies pay handsomely for the information (thus admitting that sales of CDs and iTunes tracks are a poor indication of what people actually listen to). Record companies use the information to persuade local radio stations to play what is popular. The result is not necessarily more sales — often it just means that more people download the song for free but it really helps plan lucrative concert tours. In media, metadata can be as valuable as content.

Musicians with recording contracts are starting to make their music available for free â or accept that it is free anyway. Some use free music to promote concert tours, merchandise, or albums. Radiohead famously released its album In the Rainbows for direct download and asked people to pay whatever they wanted. About 1.2 million people downloaded the album and some paid. Nine Inch Nails did something similar.

Estimates vary as to how well the Radiohead experiment worked. The high estimates assume an average price of $8, meaning the band grossed $10 million. The low estimates assume an average price of $5 with 60% not paying, so the group took in $2.4 million. Not a flop â but here is the punch line: even though the album was available for free, more than a half million users downloaded free it on a P2P site anyway. Habits are hard to break and free is a tough price point to beat. It turns out that not even free can always compete with free.

The value in music is shifting away from songs. This is hard for many artists to accept, but increasingly they will be paid for their concerts and merchandise, not their recordings. Recordings will be a way to promote concerts and merch — for free. One example of the future of digital music is Pandora, an Oakland-based “radio” that lets users select genres, but not individual songs. They pay the same pennies per song royalty that radio stations do. One can easily imagine companies licensing content on more favorable terms and making large libraries streamable over wifi, or over the cell network as bandwidth improves. This music would be free at the margin, as it is on Pandora, even if users paid a monthly subscription fee. One can easily imagine books and movies being made available on the same model.

Movies

Up next: Hollywood. Movies went digital in the 90’s, when DVDs were adopted by consumers faster than any technology in history. DVDs became a majority of movie rentals within five years of its introduction as a consumer product. Note that in each of these markets digital content is not enough — you need a very easy to use device before digital media takes off. Netflix, which mails you a DVD or three, is a very fast growing subscription service.

Up next: Hollywood. Movies went digital in the 90’s, when DVDs were adopted by consumers faster than any technology in history. DVDs became a majority of movie rentals within five years of its introduction as a consumer product. Note that in each of these markets digital content is not enough — you need a very easy to use device before digital media takes off. Netflix, which mails you a DVD or three, is a very fast growing subscription service.

Movies are now widely streamed and downloaded. In January, nearly 79 million viewers, or a third of all online viewers in the U.S., watched more than three billion user-posted videos on YouTube, according to comScore’s latest report.

Making movies for YouTube has also become much easier with the advent of low cost video cameras like the Flip, which now accounts for 30% of all video camera sales on Amazon. The little device is a point and shoot videocam that makes recording and uploading video chimp simple. I am astonished at the things one can usefully video when shooting becomes this easy.

Commercial films are already available for download at zero marginal cost. Vongo enables free downloading of studio movies for subscribers, who pay a $10 monthly fee. BitTorrent hosts and clients distribute thousands of licensed and unlicensed movies in a manner that is not economically different from P2P sharing of music files, although the underlying technology is improved. With iTunes video and cable pay per view offerings also increasing, will movie rental stores follow music stores into oblivion? Yes, they will – and fairly soon. This is why Blockbuster is trying to figure out an online streaming or download strategy (odds are not good — it’s a very different business). Your neighborhood DVD rental store is toast — and Blockbuster will go soon afterwards.

The film industry hopes that the move to Blu-ray Discs (which has now prevailed in the HD format wars, much as DVD and VHS did before them) will enable stronger cryptography to prevent free sharing of movies. It’s not going to happen. It may be technically possible to encrypt a movie in a manner than cannot be hacked, but in a war between movie studio technologists and thousands of smart 17 year olds with too much time on their hands, history is on the side of the teenagers. The industry is more likely to find ways to stream content on a pay-per-view basis, although this would disrupt lucrative deals with cable companies like HBO.

Books

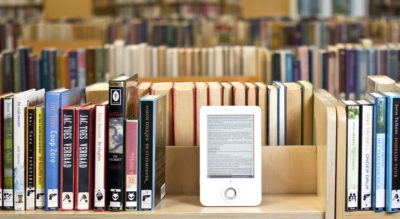

Books will be the last media to go digital for a couple of reasons. First, consumers like the analog form factor. Books are portable, shareable, resalable, and don’t require batteries. They have an emotional impact that only analog media delivers. Books sit on a shelf like Dumbledore’s Pensieve — evoking memories and old friends. You can browse them in stores in a way that is still hard to duplicate on line.

Books will be the last media to go digital for a couple of reasons. First, consumers like the analog form factor. Books are portable, shareable, resalable, and don’t require batteries. They have an emotional impact that only analog media delivers. Books sit on a shelf like Dumbledore’s Pensieve — evoking memories and old friends. You can browse them in stores in a way that is still hard to duplicate on line.

That said, eBooks have advantages. They are searchable — which matters to researchers, students, technicians, and search engines that help users discover content. They can be delivered wirelessly, instantly, and cheaply. They are obviously portable.

More fundamentally, analog books are not a great business. Most books lose money for a set of reasons that are very well known. It starts with economically delusional publishers who pay advances to authors that they do not recover in sales. Books are expensive to print, transport, and store. Booksellers have an almost unrestricted right to return books to distributors – a right given to no other retailer that I am aware of. As a result, 25% of all books in the economy are moving backwards to distributors or publishers and away from retailers and customers.

Worse, 500 new titles are published each day in the US – double the number of ten years ago. Most lose money for their publisher — indeed most are read by a very small number of people (the overwhelming majority of books in university libraries, for example, never circulate at all). During the past decade, publishers have not sold more books — they have published more titles and they have raised prices. This is neither healthy nor sustainable, especially in the face of strong evidence that all reading, and the reading of books in particular, is in long term decline in most countries.

The rise of digital self-publishing (low cost e-book only publications) will only make this worse. The first books to go digital are those expected to sell the fewest copies. Lulu, Author House, Xlibris, and others have developed business models that enable authors to digitally publish specialized books (meaning books that almost nobody wants to read in the first place). Lightning Press has persuaded a large number of publishers to digitize their “back list” (books more than a year old) and and print them on demand instead of warehousing and remaindering them. As the print on demand market develops and as electronic readers like the Amazon Kindle or the Sony Reader become easier to use and affordable, people will buy obscure books either digitally (cheapest), used (cheap), or printed on demand (most expensive). Many books will never be printed at all, as the price of digital books follows music and movies to zero.

For good reason is Apple’s iTunes closely studied by people in the book industry. Apple is the first company to tightly control and seamlessly integrate five critical media assets: digital content, metadata, a retail website, distribution economics, and consumer devices. This is not simple game to execute and Apple does it in movies as well as in music. Steve Jobs has denied any interest in producing a wireless book reader to compete with Amazon’s Kindle, so you can bet that a team in Cupertino is hard at work building one (Jobs frequently claimed to have no interest in developing a phone or videos for iPods. For many people, vehement denials from Steve Jobs are the equivalent of product development announcements).

Digital book content is not especially hard to come by. Amazon has scanned or acquired digital copies of hundreds of thousands of books, as have Google, Microsoft, and Lightning Press (although not all of these scans are of commercial quality and most do not contain resale rights). Amazon has high quality metadata (bibliographic information about the book) but this most of this data is commercially available to competitors. Amazon has a retail website, although it is optimized for physical, not digital goods and Amazon has actually lost share as a music retailer due to a weak download offering. Amazon set a $10 price point for digital books, which looks to me to be $3 too high, and Amazon’s wireless Kindle, although popular, is klutzy by Apple standards.

So figure that an iBook is on the way – perhaps a jacket pocket version of the MacAir or a larger iPhone or both. Apple is likely to come out with a better device and a more functional website, but Amazon learns fast, knows e-commerce better than anyone, has powerful metadata, and knows the publishing community better than Apple does. An alliance between Lulu or Lightning Press and Apple would surprise nobody – especially since Amazon has acquired a print on demand company, BookSurge, and now requires that all POD books use BookSurge as a condition of appearing on its retail website. This has produced the predictable uproar among authors (which must make Steve Jobs laugh. It would never occur to him to sell a media product on his website that he did not fully control).

Will digital books become free? Many already are free — specifically books whose copyrights have expired. But without a reader that is as easy to use as an iPod or a DVD player, a digital copy of a book is not worth much. Once we have a reader that is easy and fun to use, free books will proliferate. Unlike CDs and DVDs, hard copy books will not vanish any time soon, even though many small bookstores and large bookstore chains are doomed to the fate of their music brethren. Regional bookstores with scale will survive – and they tend to be the best bookstores now anyway.

All media wants to be digital and free at the margin. A writer, a musician, or a filmmaker has never been an easy vocation and will be less so as technology makes it a widely accessible avocation. Those who are used to selling books, movies, and music are in for a shock – digitization has devalued their products and trying to prevent or reverse this trend is silly and counterproductive. We can and surely will debate whether this is creative destruction or just plain old destruction – but media products will be increasingly available for free regardless of one’s view of the trend.

The result will be dozens of new business models. In music, concerts are becoming a huge business – rapper JayZ (who names these guys?) is reportedly about to sign a $150 million deal with a concert promoter instead of a record label. Ozzfest, the annual heavy metal, hard rock tour and festival founded by Ozzy Osbourne and his wife Sharon makes more money now that the concerts are free because the promoters and the bands do very well from sales of food, merchandise, and yes CDs sold at the concerts.

Behind the new business models will be dozens of new ways to acquire media. When I was a kid, I could consume video content only by watching commercial television or going to the movie theater. Today you can still watch commercial TV or go to the cinema – although it is likely now a cineplex showing a more movies to smaller audiences. Or you can record TV on your TIVO and skip the ads, you can subscribe and watch the show ad-free on cable, you can pay-per-view, you can buy a DVD new, buy one used, you can download a podcast, you can borrow a DVD from a library, rent it from Blockbuster, download it from Vongo or a P2P site, subscribe to Netflix, stream it on iTunes, YouTube, or MySpace, etc. In some cases, you pay for your content â in others (P2P, libraries, YouTube, Tivo) you watch advertising.

The result is an explosion of choices and a hugely increased chance that you will produce as well as consume media. Consumers today would never dream of trying to watch every movie available, listen to every song, or read every book. You have to go back to Thomas Jefferson to find a President who could have read every book available in English during his lifetime. Franklin Roosevelt could have listened to every bit of music recorded during his lifetime and Jack Kennedy could have watched every movie. Today a person is almost as likely to create as consume writing, movies, and music during their lifetime. This is only possible because media is increasingly digital and at the margin, free.