Every year at this time I make a habit of watching the finest business presentation on the planet: the Steve Jobs keynote address at Mac World. The event is held nearby, but I watch the film to see Jobs present new results, products, and businesses. On Tuesday Jobs gave the keynote to MacWorld 2007.

Steve Jobs is one of the great pitch-men of all time. He quivers with excitement about his products and levitates his adoring audience. For the last decade, he has made better use of graphics than any speaker I’ve seen. No lame PowerPoint here — just a single number that is two-stories high, then fade to black so the spotlight can return to Steve — where everybody wants it to be. Jobs is a spellbinder, a corporate rock star with a hypnotic hold on his faithful and the magnetism to draw in his most resolute skeptics.

All of us who are technology entrepreneurs secretly wish we were like Steve — and many other people do as well. Having on two occasions seen them together in small groups, I think that even Bill Gates wishes he was Steve Jobs — especially since Jobs’ keynote at MacWorld completely upstaged Gates’ awful speech about “digital lifestyles” at the massive Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas.

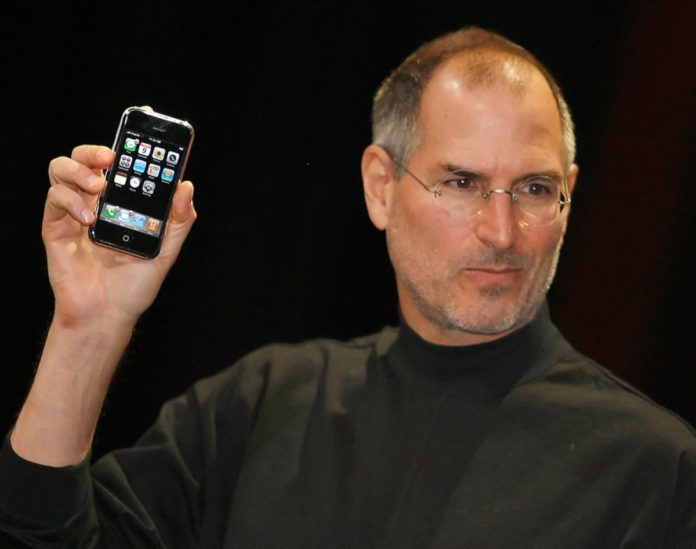

Once again his Steveness appeared badly shaven in his trademark jeans, black turtleneck, running shoes, and water bottle. He delivered a multi-media masterpiece, mixing film clips, product demos, phone calls, photo montages, music, VIP visits, and voice mails from his board member Al Gore. It helped, of course, that Jobs was announcing the coolest electronic gadget ever — Apple’s new iPhone. Thousands of middle aged dweeby white guys were throbbing with techno-lust by the end of this presentation.

We want our iPhones. Very. Very. Badly. Apple’s stock rose 8% on Tuesday — and Nokia, Motorola, and Blackberry all fell about 8%. If the iPhone works, that’s just the start.

For reason is Steve Jobs referred to as the Babe Ruth of Silicon Valley. The Apple II, Macintosh, iPod, and iPhone are each revolutionary products. Most are radical not because of new features but because the products have strong personalities that create an entirely new experience for technology users. The personality of these products — both their legendary strengths and weaknesses — is a direct expression of the remarkable Mr. Jobs.

Beyond Apple, Jobs built NeXT Computing and Pixar — which are also transformational companies. Our great grandchildren will study this guy both for his genius and potentially for his blind spots. Fortunately, Steve has been captured on video at each stage of this remarkable journey.

APPLE II: 1976

During the Carter Administration, I was newly married, living in San Jose, and working as a machinist in Sunnyvale. I had heard about a guy in nearby Cupertino who was selling a computer he called an Apple — after the fruit that landed on Sir Isaac Newton’s head, allegedly giving him critical insights as to the nature of gravity. I remember driving to Cupertino to get one and seeing the fabled Apple logo for the first time. The machine had been out for awhile, but was still a hobbyists device and not widely used (Apple II sales took off after Dan Bricklin wrote Visicalc for it in 1979). The beige computer was gorgeous — it had 8k of memory, no hard drive, and no floppy disk drive — less power than many pocket calculators. It cost a lot more than the car I drove it home in. My new wife was not impressed.

We wrote our own software or we loaded programs from cassettes using an ordinary tape recorder. (OK, after a few weeks, I was able to write a BASIC program that could count to ten all by itself. Programming is hard).

Soon Apple introduced a floppy disk drive — it held perhaps 200k and cost $400 — a couple of week’s pay for me back then. I bought Visicalc the moment it came out (and used it to build models of young Silicon Valley companies I was trying to unionize. Apple was always high on the list). Eventually I bought a Z-80 card so that I could run WordStar under an operating system called CPM (an OS that was soon purchased by a geeky kid from Seattle who had scored a contract to write an operating system for IBM’s personal computer). Years later I mentioned the Z-80 card to Jobs when I was seated next to him on a flight. It was like I had told him that I painted the computer blue: “why on earth would you do that?”. “Because you put slots in the motherboard and left the architecture open — something you have never done since” apparently did not qualify as a good answer. Bozo test flunked.

I loved the Apple II — with its weird green phosphorous screen and phone coupler to let the machine talk by phone with other computers. It had a personality that came directly from its creator — a working class valley kid with an attitude and a real knack for product design. I also loved that you could buy third party software like Visicalc and hardware like the Z-80 card. The Apple II may look like a toy today, but it was the source of so many “omygod” moments that you knew that this little device and its successors were going to change everything. It proved to be Steve Jobs’ last open architecture product however — and until I bought an iPod two years ago, it was the only Apple product I ever owned.

Here is Steve in an early commercial for the Apple II

MACINTOSH: 1984

The first most of us knew about this computer was an advertisement that appeared out during the 1984 Super Bowl that many believe is the best TV commercial of all time. It ran once — and if you saw it, you didn’t forget it. Here it is:

Shortly after he ran the ad, Jobs introduced the Mac. It had gorgeous graphics, beautiful typefaces, and an even stronger personality than the Apple II. It was the product of a process so secret that it was housed in an off-limits building that flew a pirate flag (the product was code named “Macintosh”. The team grew attached to the name). The Mac pioneered the graphic user interface, typefaces, windows, and a mouse (Well, Jobs borrowed all of these ideas from Doug Englebart at Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center and forgot to return them. Then again, Gates borrowed them from Jobs — and PARC wasn’t doing anything with the ideas anyway — they were sort of lying around).

Watch Jobs roll out the MacIntosh in this brief clip here. He clearly loves this technology — it’s incredibly touching.

By 1984, personal computers had been out for three years. They were clunky machines even then, but they did lots of things and did them pretty well. We had spreadsheets, word processors, databases, and even had basic modems which were slow and stupid, but you could dial up bulletin boards and swap software with a friend if you spent enough time fiddling with the communication protocols.

So why a Macintosh? Why a computer built on proprietary hardware that ran only software built or certified by Apple? Why release a computer that had such a small market share that talented developers wouldn’t code for it if they could? Why release a product that is fully controlled and proprietary when IBM / Intel / Microsoft had built a platform that ran on hardware available from dozens of companies and supported software written by tens of thousands of developers? Was the Mac the product of smart entrepreneurship or an act of brazen egotism? And was IBM/Microsoft or Apple the Orwellian control-freak? Jobs explained his rationale in a brief interview: “Microsoft has no taste — and I don’t mean that in a small way, I mean it in a big way”

The Mac was revolutionary, but it was a failure. Microsoft copied its strengths well enough to make Macs irrelevant to computer markets during the 80s and 90s.Like the iPhone announced this week, the Mac was very expensive and like the iPhone and the iPod, the Mac was a closed environment, not an open platform. Relatively few programmers wrote code for it, not simply because it was a smaller market, but because Apple actively restricted its expandability, controlled hardware manufacturing, and discouraged independent software developers. It was slow running some applications and pathetically slow to engage in the chaotic, emerging world of online dial-up bulletin boards. On the other hand, it was elegant, the limited software ran very well, and the beast seldom crashed or got infected.

When Mac sales fell well short of Jobs’ predictions and upgrades promised by Jobs and his team did not release on time, the CEO Jobs had hired to run Apple removed him from the Macintosh group. Jobs appealed to the board, which he chaired, but within a year of the launch of the Mac, the board fired him. Steve Jobs was not yet thirty years old.

Being fired from a company he had founded and led was a massive public humiliation. In commencement speech he gave last year at Stanford, Jobs described the experience as one of the three formative experiences of his life (along with dropping out of college and learning that he had terminal pancreatic cancer). His brief speech has become famous for its deep honesty about what matters in life and what has mattered in Jobs’ life.

I recommend it highly — it’s a great talk and my kids have been forced to read it or hear me talk about it so often they can almost recite it. Watch the address below.

NeXT COMPUTING: 1985

Jobs did not retreat to the wilderness — instead he started two more companies. The first he dubbed NeXT — a company that produced a brilliant little box that ran an obscure version of UNIX dubbed NextStep. Like Macintoshes, it was aimed at the student market. Like Macs, they were cool — the NeXT cube was a Frog Design creation featuring a stark metallic cube. Like the Mac, they were expensive: $10,000 each. Sun Microsystem CEO Scott McNealy dismissed it as “”the wrong operating system, the wrong processor, and the wrong price” (McNealy later invested in NeXt and incorporated many of its tools in Solaris). Bill Gates was more concise, asserting simply: “I’ll piss on it”.

NeXT was the system of choice for a certain geek elite, but sales never came close to the 150,000 units per year that its Fremont factory was designed to produce. Jobs brought out less expensive models and (in a move he repeated with Macs a decade later) shifted from Motorola to Intel processors. Here, Jobs demonstrates a “digital library” using NEXT search capabilities in the years before the Internet.

One famous user of the NeXT cube was a Swiss developer named Tim Berners-Lee, who used it to create the first web server and the first web browser: the World Wide Web, or modern Internet, was invented on a NeXT cube. NeXT, which ended up a far more successful software than hardware company, paradoxically wrote WebObjects — one of the first platforms for building large-scale dynamic web applications. It became NeXT’s biggest money maker (it too is expensive — but iTunes, Dell, and BBC News still run on it).

Apple, meanwhile, went into a long decline as Macs matured and Microsoft products came to dominate the market. Soon, Apple was looking to replace its aging Mac operating system and realized that a highly secure, stable, graphically-oriented OS was essential to compete with Microsoft. The company that had exactly what they needed was….NeXT Computing. At some level, Jobs had continued to build Apple even after leaving the company.

In one of the most amazing second acts in American business history, Apple bought NeXT, brought back Jobs and he has run the company ever since. The NeXT operating system was retooled as OSX and is now the foundation of every Apple computer.

PIXAR: 1986

Shortly after founding NeXT, Jobs bought the computer graphics group from Lucas Films (of StarWars fame) for $5 million and invested another $5 million in the business. Initially Pixar was a hardware company that sold specialized animation computers. Disney was one of its largest customers, but the systems never sold all that well. To try to boost sales, John Lasseter, a former Disney animator, created Luxo, Jr., a famous animated short. Realizing that the company could produce full length animated movies, Jobs approached Disney for funding, promising the people who invented animated films that he could computerize the process of animation better than they could.

He was right. In November of 1995, Pixar released Toy Story. The film became the highest grossing film of 1995, generating $362 million in worldwide box office receipts. Toy Story’s director and Pixar’s chief creative officer, John Lasseter, received a Special Achievement Academy Award for his “inspired leadership of the Pixar Toy Story team resulting in the first feature-length computer animated film.” Here, Jobs gives a detailed historical and technical perspective on Pixar and the complexity behind Toy Story.

Pixar moved from success to success. A Bug’s Life, Monsters, Inc., Finding Nemo, The Incredibles, Cars, and Toy Story 2, all followed — and all were box office smashes, giving Pixar six of the top grossing animated films of all time.

Toy Story 2, at the time of release, broke numerous opening weekend records all over the world and won a Golden Globe award for Best Picture, Musical or Comedy in 1999.

Monster’s, Inc. reached over $100 million at the domestic box office in just 9 days, faster than any animated film in history at the time of its release.

In 2003, Pixar released Finding Nemo which broke every one of Monsters, Inc.’s opening weekend box office records that had been set only 18-months earlier. Finding Nemo generated $865 million at the global box office and received the Academy Award® for Best Animated Feature Film.

The Incredibles, released in 2004, earned more than $620 million worldwide, elevating it to the second highest grossing Pixar film and amongst the 25 highest grossing film of all time and four Academy Award nominations.

Disney was thrilled, but Jobs chafed under the terms of the deals. The contentious relationship culminated in the purchase of Pixar by Disney in January of 2006 — a deal that made Steve Jobs the largest owner of Disney by a wide margin. Walt would be pleased.

iPOD: 2001

By the late nineties, Jobs and many others understood that the business of music recording, distribution, and retailing was profoundly broken. Labels had become risk averse and hit driven, retailers had to cover costs with sales from fewer and fewer groups, and the theft of music on websites like Napster and KaZaa threatened the entire system. The music industry decided that the smartest thing it could do would be to sue its customers for illegal downloading. Hmm.

Steve Jobs saw an opportunity not simply for a better MP3 player or a better music website. He realized that he could profoundly restructure how music was sold and delivered. He had a chance to do in music what he had done with personal computing: transform the industry by using technology to set a new and higher standard.

This meant getting record labels to agree to a scheme of digital rights management of the sort they had long opposed. Jobs could not have done this as CEO of Apple — but he was now a very successful Hollywood movie executive — both the CEO of a major and very wealthy studio and the juice behind both the software and the creative talent that produced a new generation of animated films. He had effortlessly become our new Walt Disney — and he had the access, savvy, and clout to create a new deal for the music industry and a hip, classy, fully integrated offering to his customers.

The launch, which took place a few weeks after the September 11 attacks in 2001, was a watershed event for Apple — the company has grown up and to the right ever since. You can watch Jobs launch of the iPod here.

Once again, Steve Jobs’ personality pervades the product. The iPod is easy to use, stylish, and vaguely hip. It is also entirely closed as a platform. As Randall Stross explains in today’s Times Here is how FairPlay works: When you buy songs at the iTunes Music Store, you can play them on one – and only one – line of portable player, the iPod. And when you buy an iPod, you can play copy-protected songs bought from one – and only one – online music store, the iTunes Music Store.

The only legal way around this built-in limitation is to strip out the copy protection by burning a CD with the tracks, then uploading the music back to the computer. If you’re willing to go to that trouble, you can play the music where and how you choose – the equivalent to rights that would have been granted automatically at the cash register if you had bought the same music on a CD in the first place.

Even if you are ready to pledge a lifetime commitment to the iPod as your only brand of portable music player or to the iPhone as your only cellphone once it is released, you may find that FairPlay copy protection will, sooner or later, cause you grief. You are always going to have to buy Apple stuff. Forever and ever. Because your iTunes will not play on anyone else’s hardware.

Unlike Apple, Microsoft has been willing to license its copy-protection software to third-party hardware vendors. But copy protection is copy protection: a headache only for the law-abiding.

What impact has the iPod had? It has not solved the crisis of the music industry — sales of CDs are falling faster than online sales are rising. On the other hand, the part of the music business that Jobs invented — downloaded digital music — is healthy and iPod/iTunes owns about 60% of it, thanks to consumers who are willing to be locked in to a technology controlled by a single company. Why would consumers do this? Simple: songs are a buck and iPods are reliable, fun, and easy to use.

Increasingly however, music is not a product, it is a service. Some believe that in perhaps in 5 or 10 years, portable players will have wireless broadband capability and will provide direct access, anytime, anywhere, to every song ever released for a low monthly subscription fee.

It’s a prediction that has a high probability of realization because such a system is already found in South Korea, where three million subscribers enjoy direct, wireless access to a virtually limitless music catalog for only $5 a month. He noted, however, that music companies in South Korea did not agree to such a radically different business model until sales of physical CDs had collapsed.

iPHONE: 2007

Which brings us to Tuesday. Jobs announced Apple TV, which lets you show stuff from your Mac on a flat panel TV. He announced that Apple Computer changed its name — it is now just Apple, Inc. Because Apple is no longer just a computer company.

Then Jobs unveiled the iPhone. How cool is it? It’s sexy thin, runs OSX, has no keyboard but uses a Multi-Touch screen that figures out what input you need. When you need to type, there is a touchscreen keyboard. For buttons, your finger just pokes. To scroll through songs, voice or email messages, photos or contacts, it lests you flick along the bottom of the screen. You can “pinch” a photo between your fingers to expand or compact the image.

In Jobs’ words: “…multitasking, networking, power management, graphics, security, video, graphics, animation.” Like the Blackberry, it has an ambient light sensor. Like the Treo, is has a camera. Unlike either, it has a proximity sensor to shut off the touch screen when you have it against your face. It has an accelerometer to sense whether it is in portrait or landscape mode. You can watch video, listen to music, manage contacts, scroll through contacts, pick which voice mail to answer, get cool album art. Jobs said Apple has filed over 200 patents related to the phone.

Retrieving voice mail is easier because you can touch only the message to want to hear, so you can pick which message you want to listen to first rather than listen to them in order. Jobs said the iPhone’s virtual onscreen keyboard is better for typing than most of the plastic tiny keyboards in most smartphones. It wouldn’t take much, but he poked with his finger instead of typing with his thumbs. Hmm.

Connectivity includes quad-band GSM, EDGE, all three Wi-Fi protocols — 802.11b/g and the forthcoming 802.11n — as well as Bluetooth 2.0 and EDR wireless. Cingular will be Apple’s exclusive partner under a multiyear agreement (Cingular got the exclusive distribution rights by signing a deal two years ago sight unseen.) The 4GB iPhone will run $499 and an 8GB version will be $599. Available in June.

Ominously, my 14 year old was not impressed.

“Look, they didn’t use the 3G network, how lame is that?

“Also, it’s another closed Apple platform — you won’t get much software for it” (he despises Sony for crippling his PS2 this way).

“Your Blackberry lets you open attachments and edit documents or spreadsheets” (well, sort of) — “the iPhone won’t”.

“Plus, the lawsuit with Cisco over the name makes them look stupid”.

The kid is right, of course. Jobs is just not a Web 2.0 kind of guy — and never has been.

User generated content? I don’t THINK so! You want an iPhone, it’s just like an iPod or a Mac — you get it Steve’s way. You can enter Steve’s world or you can stay out — but you cannot modify it in any way. In Steve’s world, there is one visionary, a lot of developers, and millions of users.

Not for him any talk of open systems, turning consumers into developers, or platforms for participation. Jobs quotes computer scientist Alan Kay to the effect that “People who are really serious about software should make their own hardware.” Well, if you want to run a few programs and have them execute flawlessly, this is hard to argue with. If you want to promote innovation by turning loose tens of thousands of developers, it is a less interesting approach.

The problem is that software is migrating rapidly from the desktop to the web. The value of an open system that can support thousands of programs is diminished in a world where a browser can support thousands of websites and a small number of tasks need to work in an integrated way. This environment plainly favors Apple — just as the 1980s and 90s favored Microsoft.