Cities concentrate people, wealth, culture, and memories. In New York this week, I walked by an Indian restaurant and recalled a lunch almost twenty years earlier with friends who tried to persuade me to come work on Wall Street. Across from the restaurant stood a former men’s club where I pitched an IPO fifteen years later and 50 feet further along sat a hotel that I had once lived in for a month as a consultant. These were a trivial fraction of the memories millions of people have of this fairly ordinary midtown block.

At the end of the week, I passed very briefly through Paris. I had a single free evening and realized that it had been exactly thirty years since I spent seven months in Paris studying and wandering. I had been inspired by Hemingway’s famous claim that “to be a young man in Paris is a movable feast”. When I arrived in 1977, my feast was cold and rainy. I headed to point zero — the official center of the city in front of the Cathedral Notre Dame. On Friday, I retraced my steps.

Cathedrals, especially old, complete European ones, store memories as well as values. I remembered staying late at Notre Dame, listening to choral music with my backpack at my feet, happy for shelter and warmth after a long flight. Eventually however, I had to face a disconcerting reality: I had no place to spend the night. My savings of $2,000 had to last many months. I wandered perhaps 100 yards from the cathedral and came to 37 Rue de la Bucherie, sort of an extension to Notre Dame — a bookstore I had never heard of that has greeted wanderers for more than half a century. It is a cathedral of books — a bookstore unlike any other in the world (its closest companion, City Lights in San Francisco, is a hip pretender by comparison — as its name all but acknowledges).

On that drizzling night in 1977, I discovered Shakespeare & Co, and I met George Whitman, its proprietor, then 64, who built the store and had run it for 26 years. George was a grizzled, mischievous, slightly formal bookman. He greeted me and inquired as to my intentions. We talked books, poetry, politics, and writing. We discussed my travels in China, and it emerged that he had traveled very widely in the years before I had been born. Soon it was late. He offered me soup — not terrific soup as I recall — but warm and welcomed under the circumstances. Did I need a place to stay? Well, um, yes. He pointed me upstairs, where I discovered a maze of a bookstore store with reading nooks that served as cots at night. As midnight approached and the store closed, I realized that several other young people were preparing to sleep amidst the books.

On that drizzling night in 1977, I discovered Shakespeare & Co, and I met George Whitman, its proprietor, then 64, who built the store and had run it for 26 years. George was a grizzled, mischievous, slightly formal bookman. He greeted me and inquired as to my intentions. We talked books, poetry, politics, and writing. We discussed my travels in China, and it emerged that he had traveled very widely in the years before I had been born. Soon it was late. He offered me soup — not terrific soup as I recall — but warm and welcomed under the circumstances. Did I need a place to stay? Well, um, yes. He pointed me upstairs, where I discovered a maze of a bookstore store with reading nooks that served as cots at night. As midnight approached and the store closed, I realized that several other young people were preparing to sleep amidst the books.

I stayed with George for the three weeks it took me to get settled in Paris and I visited the store often thereafter. George asked only that I help out a bit and “read a book every day”. Some time later Whitman confided that “Shakespeare & Company was less a business than “a socialist utopia masquerading as a bookstore”.

I discovered that my experience was not at all unusual. George had been inviting people to sleep in one of the 13 beds among the books since 1951. He calculates that more than 50,000 people have stayed at his “Tumbleweed Hotel” at one time or another. The figure seems entirely plausible.

YouTube has dozens of video tours of the store. This one features a fairly characteristic interaction with George shot around the time of this visit.

I remembered these things as I approached the entrance to the store at dusk tonight. Bins of cheap books still sit outside. The the same beat up desk still commands the door like the bridge of a ship. I recalled George tending the cash box, answering questions, and drinking tea from chipped glasses. The store is still a warren – both a treasure house and a fire trap — a place that Henry Miller once called ‘a wonderland of books’. The small antiquarian room still sits locked, available only to trusted friends. I had spent time in it towards the end of my stay and coveted a signed, illustrated first edition of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle. I was amazed that anybody would pay $30 for a book. The room was a time capsule — I discovered signed and often inscribed volumes from hundreds of famous authors — most of whom had passed through and stopped at the shop.

So tonight I asked, more tentatively than in past visits, whether George was still around. I knew that he would be 94 if he were still alive and presumably at the end of an amazing life. I realized that he was the same age as Henry Groues, by a large margin the most popular man in France. Known to all as Abbe Pierre, Groues evolved from a champion of the French resistance to an unrelenting and very effective advocate for the Parisian homeless. He had died at age 94 a week ago. France was still mourning the death of a man even the secular French regard as a saint (Le Monde published an unprecedented 18 page obituary recalling, among other things, how his plea for clothing and blankets during the winter of 1954 led to such a mountain of donations that it overwhelmed an abandon French train station). I wondered — had George had outlived his soulmate and compatriot?

George was a saint of a different sort. The son of a Boston physicist, he had traveled the world with his father, settling in France and deciding to open a bookstore three years before Abbe Pierre overwhelmed the Gare D’Orsay. Writing in the London Observer, Michael Hayward recalled that

“By 1951, George Whitman had already spent five years in the area, and fallen in love with ‘the cultural capital of the world’. A Boston native, his childhood had been spent globe trotting with his father, a traveling physics professor. After studying for a degree in journalism at Harvard, he set off on a seven-year, proto-hippie trek through North and South America. More than 50 years later, he can still remember meals he ate and people who fed him. It was this journey, he says, that shaped his politics and social conscience, opening his eyes to stark differences between his homeland and its poorer neighbors.”

After Latin American studies at Harvard and two years with the Merchant Marines during the Second World War, he had sailed for Paris in 1946 to work in a camp for war orphans. When it disbanded, George, now in his mid-thirties, enrolled to study French Civilization at the Sorbonne.War veterans could claim a handsome book allowance by submitting receipts to the Veteran’s Association. He made good use of this perk, and his tiny room in the Hotel de Suez, on the boulevard St Michel, was soon lined with books on literature, philosophy, politics and history. “In those days,” he recalls, “there was a shortage of everything, so books were precious, valuable, highly sought-after things.”

His library soon became a meeting point for like-minded expatriates, and since it had no lock, (George) often returned to find strangers reading in his room. Glad of the company, he would invite them to stay for dinner. Another ex-serviceman, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, (later a beat poet and founder of City Lights in San Francisco) arrived in Paris in 1948 to study for his doctorate in poetry at the Sorbonne, with a letter of introduction from George’s sister, whom he had met at Harvard.”He was living in this little 8 foot by 8 foot room,” remembers Ferlinghetti, “no windows, and books stacked up to the ceiling on three sides And there was George in the middle, reading in this broken-down armchair.”

In 1951, backed by a small inheritance, George returned to Paris and took a room above an Arab grocery store. He slowly built a bookshop he named Les Mistral (the cold, arctic winds that visits Europe in the winter. By ancient French law, anyone who claims to have gone mad on account of the sound of the Mistral may be pardoned of their crime, including murder). At the fiftieth anniversary of his store in 2001, he recalled

“this area in the heart of Paris was crammed with street theater, mountebanks, junkyards, dingy hotels, wine shops, little laundries, tiny thread and needle shops and grocers. Back in 1600 in the middle of this slum our building was a monastery with a frère lampier who would light the lamps at sunset. I seem to have inherited his role because for fifty years now I have been your frère lampier.”

Was George still lighting lamps?

I remembered the wonderful history of his store. George had started Les Mistral a short distance from the original Shakespeare & Company, a bookstore that had become famous in Paris. The original store was run by an American expat named Sylvia Beach, who became George’s inspiration and spiritual mentor. By World War II, Beach’s store was renowned as the gathering place of a loose group of writers known later as the Lost Generation. Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, Ezra Pound, F. Scott Fitzgerald, John Dos Passos, and Gertrude Stein all smoked, wrote, and debated in Left Bank cafes. This generation of avant garde writers had been drawn to the freedom of Paris in no small part because the Napoleonic Code had decriminalized homosexuality many years earlier, so gay artists and writers had long preferred Paris to New York or London.

Beach had become famous, and infamous, in 1922 for publishing a huge, difficult novel that takes place during a single day in Dublin written by an obscure writer with a nonlinear style. Several publishers had declared the book unreadable (and my sympathies are with them) but Beach thought it brilliant. The book was Ulysses, by James Joyce — and it was quickly banned in both the United States and the United Kingdom, which of course made Joyce and Beach both famous.

Beach was forced to close shop when the Nazis occupied Paris (allegedly her store was ordered shut because Beach denied a German officer the last copy of Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake.) She put her most valuable books into storage, before being sent to an internment camp but was released by the Vichy government and returned in time to see Allied troops fighting their way into the city.

One of the finest stories of the liberation of France has it that one of the first allied jeeps into Paris was commandeered by a bearded war correspondent who made a beeline for Shakespeare & Company. The store was located at 12 Rue de l’Odeon, not far from the Jardin du Luxembourg. With shells still exploding and cleanup combat still underway, Sylvia Beach heard the correspondent call her name from the street. It was Ernest Hemingway.

“I flew downstairs,” she later recalled, “We met with a crash; he picked me up and swung me around and kissed me while people on the street and in the windows cheered.”

Beach never reopened her store. But just as the Lost Generation had gathered before the war at Shakespeare & Company, the Beat Generation — a new group of postwar avant garde writers gathered at Les Mistral. George held readings, published a small literary magazine called Merlin, and hosted writers such as Eugene Ionesco, Allen Ginsberg, Jean-Paul Sartre, William Burroughs, and Samuel Beckett before they were widely known. Burroughs used George’s medical book library in writing Naked Lunch.

When Beach died in 1964, George re-christened the store Shakespeare & Company. At age 70, five years after I met him for the first time, he fathered a daughter and named her Sylvia Beach Whitman. Today, Sylvia runs the bookstore with her father’s verve and politics combined with a feminine and feminist touch. I’d give long odds to the women writers in their twenties I noticed hanging out at Shakespeare & Co. courtesy of Sylvia.

If the movable feast that brought me to Paris thirty years ago had a headquarters, it was Shakespeare & Co.– but I recognized that the odds weren’t es

If the movable feast that brought me to Paris thirty years ago had a headquarters, it was Shakespeare & Co.– but I recognized that the odds weren’t es

pecially good that George Whitman would still be alive.

“Oh, he’s very much still living” replied the 20 year old woman behind the register (and I’d bet money that she had a sleeping bag stashed under a sofa upstairs).

Would he like to see an old friend? “Absolutely!” — and she unlocked the door to the stairway leading to his third floor apartment.

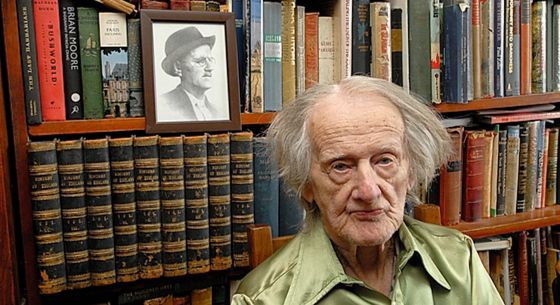

George was always old — but now he is good and old. A few years back some guys made a movie about the end of Whitman’s days called Bookseller As an Old Man. The movie captures one of George’s many peculiar habits — he has been known to trim his hair by lighting it on fire with a candle. It produces a look that can only be described as antiquarian punk. It hadn’t been lit in awhile — it was nearly shoulder length and pure white. He lives as he has for more than fifty years above his shop in a small apartment with a window overlooking Notre Dame.

George’s place is a bibliophile’s heaven. Books on every wall, every table, and much of the floor space. The building is a former 15th century monastery and needs maintenance (it only gets what the city requires because, like many booksellers, George has no interest in managing money. More than one guest used to pull books off of his shelves only to find a pile of Francs that George had absent-mindedly stashed). A bed, a reading chair, a table with coffee cups and a bit of fruit and bread on it — the rest was thousands of books.

He offered me tea and we remembered lost times. His mind remains sharp — he recalled his trips to China as a young man and we tried to recall the reading group on China that I held at his store (frankly neither of us remember it very well). A man who often proclaims himself a communist, he complained bitterly about how useless Maoists are and how well he thinks of Chung Jang’s Wild Swans, a memoir of three generations of Chinese women. The book is is featured prominently in the store downstairs. Chung had recently come to the store and done a reading of from her well-researched but devastating biography of Mao, written with her historian husband Jon Halliday. We spent the better part of an hour together before I thanked him again for his extraordinary hospitality 30 years earlier and he thanked me for the modest help that Alibris has offered him over the years.

The truth is, George welcomes everybody, feeds everybody, and lets them stay as long as they want. One guy stayed five years — a former advertising executive who had become a drunk and turned his life around in Paris. Some who stayed, like Jacqueline Kennedy and George Soros, went on to become famous. Many, like me, have never forgotten Whitman’s generosity. As George tells it:

“When a French explorer named Michel Peissel visited the bookshop I told him I had read his book of travels in Quintana Roo and hoped someday to meet him. He told me we had already met because as a student he frequented the bookstore and the books he read here inspired him to become an explorer. In fact, he said, now that I have published eighteen books I am back where it all started in the little library above the bookstore.

I have met many booksellers in my life — it’s part of what I do. None compare with George Whitman for the love of books and writing and extraordinary human generosity. As I said goodbye, I noticed a picture of Walt Whitman above the doorway. I asked if he was related to the great American poet.

“I have always felt a strong kinship with Whitman, so I like to think so” George said. “My dad was named Walt Whitman”.

Elsewhere, George has written that Walt Whitman also ran a bookstore and printing press in Brooklyn over a century ago.

“I believe the bookstore has the faults and virtues it might have if he were the proprietor. It has been said that perhaps no man liked so many things and disliked so few as Walt Whitman and I at least aspire to the same modest attainment”

I realized that I might not see George again (he joked that he was planning to retire when he turned 100). Some years back, he published an epitaph:

“Perhaps like Ambrose Bierce who disappeared in the desert of Sonora I may also disappear. But after being in all mankind it is hard to come to terms with oblivion – not to see hundreds of millions of Chinese with college diplomas come aboard the locomotive of history – not to know if someone has solved the riddle of the universe that baffled Einstein in his futile efforts to make space, time, gravitation and electromagnetism fall into place in a unified field theory – never to experience democracy replacing plutocracy in the military-industrial complex that rules America – never to witness the day foreseen by Tennyson ” when the war-drums no longer and the battle-flags are furled, in the parliament of man, the federation of the world”.

“I may disappear leaving behind me no worldly possessions – just a few old socks and love letters, and my windows overlooking Notre-Dame for all of you to enjoy, and my little rag and bone shop of the heart whose motto is “Be not inhospitable to strangers lest they be angels in disguise”.

“I may disappear leaving no forwarding address, but for all you know I may still be walking among you on my vagabond journey around the world.

At six o’clock in the evening, Notre Dame sounded its bells as it has most every evening for centuries. From the bookstore, the sound is heavenly — and loud enough to stop all conversation. For five minutes, Paris is a small and familiar town again and I am surrounded by the life’s work of a man who believes deeply in humanity, in kindness, and the power of the written word. It is a brief, transcendent moment. I purchase a book, head into the drizzle, and find dinner at an empty restaurant on Rue de Seine. As I leave the restaurant to head home, I notice its name: Le Temps Perdu (Forgotten Times).